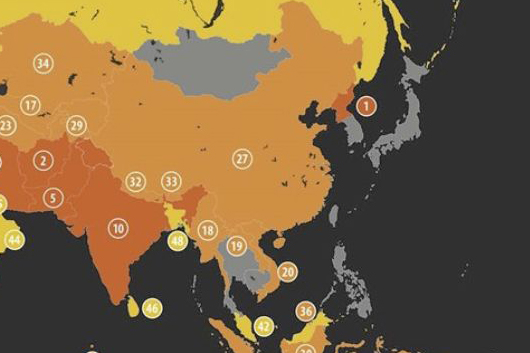

インドが2014年にトップ20入りして以来、順位は着実に上がっている。これは、現在のナレンドラ・モディ首相が就任した年だ。現在は10位で、大部分がヒンドゥー教徒の国(人口の約80%)は、生活の中での迫害とクリスチャンへの暴力で最高得点を挙げている。

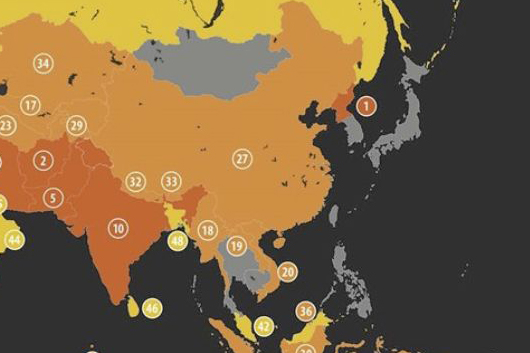

India’s place on the World Watch List has risen steadily since it first broke the top 20 in 2014, the same year current Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office. Now at No. 10, the predominantly Hindu nation (about 80% of the population) scored the highest for persecution in national life and in violence against Christians.

「ヒンドゥー教急進派によるクリスチャンへの迫害が少し弱まることを願っていたが、この望みは叶(かな)わなかった。迫害は少なくなるどころか増加している」。オープン・ドアーズによると、8つの州で反改宗法案が可決され、クリスチャンによる機関を対象とした規制が強化された。

“It was hoped that the persecution of Christians by Hindu radicals would slow down a bit … but these hopes were in vain: Hindu radicals have continued their attacks and even increased them,” according to Open Doors, which cited anti-conversion laws passed in eight states and regulations targeting Christian-led institutions.

モディ首相率いるインド人民党(BJP)は、ダリット(不可触民)やイスラム教徒、他の少数部族と同様、クリスチャンも差別の対象としている。昨年のワールド・ウォッチ・モニターによると、特にインドで最も人口の多いウッタル・プラデーシュ州では、教会建物の破壊、回心者への報復、礼拝の急襲、その他の反キリスト教的活動が慢性化している。

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been associated with discrimination against Christians, as well as Dalit, Muslim, and tribal minorities. Last year, World Watch Monitor chronicled vandalism against church buildings, retaliation for conversions, raids on worship services, and other anti-Christian activity, particularly in India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh.

インドと、5位の隣国パキスタンは、トップ10中、最も高いレベルで暴力が行われている(ナイジェリアと中央アフリカ共和国が続く)。

India and its neighbor Pakistan, which ranked No. 5 on the overall list, have the highest levels of violence among the top 10. (After Pakistan, Christians in Nigeria and the Central African Republic experienced the most violence last year.)

中国は教会生活の分野で最悪となっていて、オープン・ドアーズは次のように述べる。「現在、政府だけでなく共産党によって宗教管理がなされており、政府公認の教会も非公認の教会も圧力を強く感じている」

China scored its worst in the category for church life, with Open Doors noting that “the management of religious affairs lies with the Communist Party now, not just with government, and Christians are feeling this strongly … in both state-approved and non-registered churches.”

2018年、中国はオンラインでの聖書販売を制限し、教会の監視を強制しようと試み、3つの有名な地下教会を閉鎖し、指導者を拘束した。

In 2018, China restricted online Bible sales, attempted to force surveillance on churches, closed three prominent underground congregations, and detained their leaders.

昨年末、中国共産党に急襲されて逮捕された秋雨聖約教会(成都市)の王怡(おうい)牧師は、「私の神への忠誠ゆえの不服従に関する宣言文」で次のように述べている。「この共産主義体制による一時的な統治は神によって許されているという事実を私は受け入れ、尊重する。……同時に、この共産党政権の教会に対する迫害は非常に邪悪な違法行為だと確信している」

“I accept and respect the fact that this Communist regime has been allowed by God to rule temporarily. … At the same time, I believe that this Communist regime’s persecution against the church is a greatly wicked, unlawful action,” wrote pastor Wang Yi, who was arrested late last year after officials raided Early Rain Covenant Church in Chengdu, in a viral letter on his faithful disobedience.

王怡氏の拘束と同じ頃、南部バプテスト協議会の倫理・信教の自由委員会でキリスト教倫理上級研究員を務めるアンドリュー・ウォーカー氏は、中国と北朝鮮における宗教的迫害の被害者を弁護するため、ジュネーブの国連事務所を訪れた。

Around the same time as Yi’s detention, Andrew Walker, senior fellow in Christian ethics for the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, traveled to the United Nations office at Geneva to advocate for victims of religious persecution in China as well as North Korea.

「権力の統合を常に求める中国のような悪名高い人権侵害国では、宗教的迫害の拡大は、キリスト教への取り締まり以上に広範囲で起きている反民主主義的運動の一部と見ることができる」とウォーカー氏は語る。

“When it comes to a notorious human rights offender like China, a country always interested in consolidating power, it’s possible to see the rise of religious persecution as a part of a broader, growing anti-democratic impulse to crackdown on the growth of Christianity,” said Walker in a statement to CT.

「権力を統合し、異論を排除することが政治体制のための主目的であるとき、一般的に宗教、特にキリスト教に刃(やいば)が向けられる」

“When consolidating power and erasing dissent is the name of the game for a political regime, you can always count on religion in general, and Christianity in particular, to be a victim.”

オープン・ドアーズによると、信教の自由が制限されている国々で「被害者」クリスチャンの立場は改善されていない。上位10位の国では、迫害が増えたか、慢性的に継続している。

According to Open Doors, Christianity’s “victim” status among the most severe violators of religious freedom isn’t improving. Each country in the top 10 either scored higher for persecution or held steady over the past year.

「ワールド・ウォッチ・リストや他の宗教自由度をはかる資料によって、たとえ否定的な傾向が継続的に明らかになったとしても、それらが国際的に大きく取り上げられることで、海外の政府の力が世界の教会にどのように影響するかを理解する手段となる」と述べるのは、キリスト教迫害の専門家で聖書民族改革派神学校研究室長のK・A・エリス氏。

The annual World Watch List and other measures of religious freedom—even when they continually reveal negative trends—can serve as a tool for Christians to process international headlines and better understand how government forces abroad affect the global church, according to K. A. Ellis, an expert in Christian persecution and the new director of the Center for the Study of the Bible & Ethnicity at Reformed Theological Seminary.

「このようなリストは、キリスト教に敵対的な地域でも教会開拓を支援する責任を持たせ、『その地域を世界から切り離すことはできない』という意識を広げることになる」

“I’ve also seen such lists foster a burden to support church planters in a hostile region, either on one person or a congregation’s heart, expanding our understanding of how the local and global are inseparable,” she said.

西欧のクリスチャンに対し、迫害の程度を誇張したり、クリスチャンの窮状を強調したりすることによって、キリスト教ではない少数派の窮状を無視することについて、ケンブリッジ宗教国際研究所のマネージング・ディレクターであるジャッド・バードサル氏が最近、警告した。

Judd Birdsall, managing director of the Cambridge Institute on Religion and International Studies, recently cautioned Western Christians against pitfalls of combating persecution, including exaggerating the extent of persecution if they don’t understand how it’s being measured as well as overemphasizing the plight of Christians while neglecting the plight of non-Christian minorities.

「概してワールド・ウォッチ・リストは、世界中の迫害された兄弟姉妹を支持し、祈るよう、クリスチャンに働きかけるのに役に立つと思う」

“In general, I think the World Watch List is a useful and engaging way to encourage lay Christians to support and pray for their persecuted brothers and sisters around the world,” he told CT by email.

「多様な観点から信教の自由に関するレポートをたくさん用意しておくと、さまざまな人が参加することができ、複雑かつ多面的な世界的問題をより深く理解するのに役立つ。一つの報告書によって、仲間のクリスチャンの苦しみとその複雑さを説明することはできない。クリスチャンが社会的緊張を悪化させ、差別を容認することさえあるからだ」

“It’s useful to have lots of religious freedom reports coming from lots of different perspectives so that we can engage a variety of audiences and come to a fuller understanding of a complicated, multi-faceted global problem,” Birdsall added. “No one report can capture all of that complexity.” He noted that though the report illuminates suffering by fellow Christians, its scope doesn’t allow believers to also consider places where Christians “exacerbate social tensions and even condone discrimination.”

「クリスチャンの苦しみだけに焦点を合わせると、国際的な宗教的迫害と不寛容の重要な側面を見逃す」

“To focus only on the suffering of Christians is to miss that crucial dimension of international religious persecution and intolerance,” he said.

オープン・ドアーズは、他の宗教的マイノリティーとクリスチャンの間で迫害がどのように共有されているかについて言及した。それは、過去1年間、宗教の自由に向けて実際に著しい進歩を遂げたイラクとマレーシアを含む。

Open Doors mentioned how persecution in certain countries is a fate believers share with other religious minorities, including in two of the countries that actually made significant progress toward religious freedom in the past year: Iraq and Malaysia.

イラクはイスラム過激派「イスラム国」(IS)が後退したため、全面的に迫害が減少し、13位に下がった。また2018年、予想外に勝利したマレーシアの新しい政党連合は、クリスチャンと他の少数民族によって歓迎された。新政党連合の希望連盟(Pakatan Harapan)は、クリスチャンのトミー・トーマス氏を検事総長に任命している。前編を読む

Iraq dropped out of the top 10 to No. 13, due to the retreat of ISIS from the country, which led to a drop in persecution across the board. Meanwhile Malaysia’s new political coalition was celebrated by Christians and other minorities after its unexpected victory in 2018. The newly elected Pakatan Harapan even appointed a Christian, Tommy Thomas, as attorney general.

執筆:ケイト・シェルナット

本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。

出典URL:https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2019/january/50-worst-christian-persecution-open-doors-world-watch-list.html

「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(Christianity Today)は、1956年に伝道者ビリー・グラハムと編集長カール・ヘンリーにより創刊された、クリスチャンのための定期刊行物。96年、ウェブサイトが開設されて記事掲載が始められた。雑誌は今、500万以上のクリスチャン指導者に毎月届けられ、オンラインの購読者は1000万に上る。

関連