数年前、まだ幼稚園児だった息子のクインは、クリスマスの朝にプレゼントを開けて落胆し、私を見上げて、「(返品のために)レシートはある?」と聞いた。私は「感謝することを教えなければ」と思った一方で、息子の言葉の中に大多数の人の本音を感じ取っていた。私たちは命というプレゼントをもらっているにもかかわらず、包みを開けてみると、中には返品したいような部分もあるのではないだろうか。

Several years ago, when my son Quinn was in kindergarten, he opened a present on Christmas morning, and he was not happy with what he saw. He set it aside, looked up at me, and declared, “We’re gonna need a receipt for that one.” I made a mental note to start working on gratitude with him as soon as the wrapping paper was all picked up. Yet, at the same time, I heard in his words the ordinary wish of the masses of humanity: We are given this gift called life and, oftentimes, as we unwrap it, there are parts of it we would like to return.

ホントホルスト「羊飼いの礼拝」(1622年)

だいたい苦痛に関しては、レシートがほしいものだ。

Usually, we want a receipt for the painful parts.

数カ月前、クインが5年生になる最初の日、息子を学校に送っていって下ろしたあと、同じように親たちの車の列がゆっくり進んでいたので、息子が校庭に入るところが見えた。ひとりぼっちで、緊張した様子でバックパックのひもをいじっていた。

クインは子どもたちの輪の中に友達の顔を探したが、見つからなかった。私は胃が縮んだ。心理学者としては、子どもはこのような経験を乗り越える必要があることは分かっている。しかし父親としては、息子のそばに行きたかった。だが車列は進み始め、結局、私は息子を残していかなければならなかった。

息子は「そのうち」友達を見つけるだろう。いつまでも一人ということはない。だが私は、「そのうち」では不満だった。苦痛はパスしたいのだ。

For instance, several months ago, I dropped Quinn off for his first day of fifth grade. The long line of cars was moving slowly, so I had time to watch him walk onto the playground. He stood there, alone, nervously rubbing the straps of his backpack, scanning the crowd for just one friendly face. He turned in circles and searched in vain. My stomach clenched. As a psychologist, I know kids need moments like this to build resilience—to learn they can survive it—but the father in me was about to pull over and get out anyway. Then, the line sped up and I was forced to move on, leaving my son lonely and looking. I knew he’d eventually find his friends—moments of loneliness always precede moments of belonging, that’s just the way it is—but eventually wasn’t good enough for me.

I wanted to skip over the painful part.

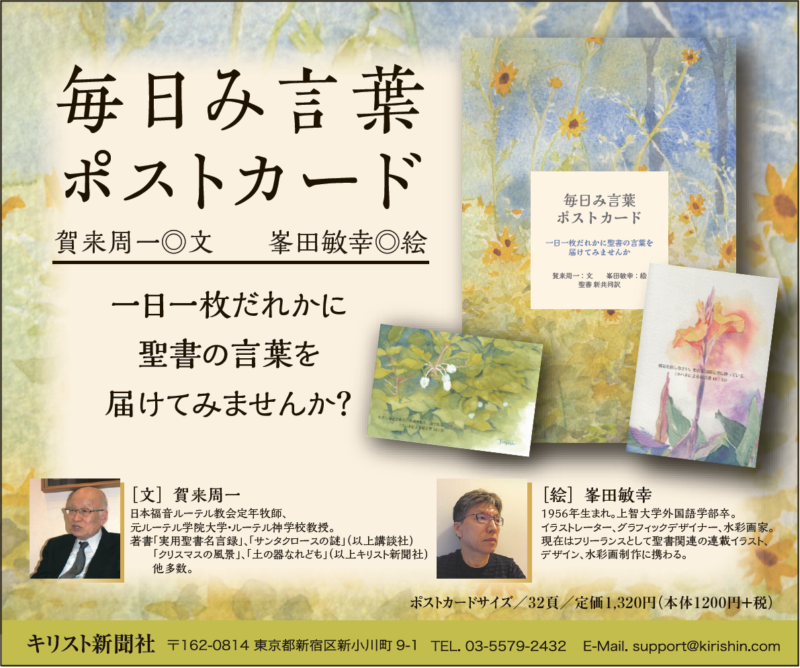

イエスは涙を流された

子どもたちが願いごとのリストを作り、クリスマス・ページェントで賛美し、アドベント・カレンダーを開くのを見守りながら、私は自分の子ども時代のクリスマスを思い出す。クインと同じ年ごろに通っていた教会で、私はつらい時にどう対処するかを学んだ。毎週の教会学校で聖書を学んだが、今でも鮮明に覚えていることが一つある。「聖書で最も短い節は?」の答えが「イエスは涙を流された」(ヨハネ11:35)ということだ。

It’s Christmastime now, and as I watch my kids make wish lists and sing in Christmas pageants and open an Advent calendar, memories of my own childhood are revived, like ghosts from Christmases past. Specifically, I recall the church I attended when I was Quinn’s age, where I learned about a better way to handle the painful parts of life. Every week in Sunday school, we’d practice Bible trivia. Over time, I memorized most of the questions and answers, and for some reason, to this day, I remember one question in particular: “What is the shortest verse in the Bible?” And the answer?

“Jesus wept.”

なぜイエスは涙を流したのか。

物語は、ラザロの姉妹がイエスのもとに人をやって、「主よ、あなたの愛しておられる者が病気なのです」と伝えるところから始まる(3節)。イエスは答える。「この病気は死で終わるものではない」(4節)。その後、イエスはしばらくそこにとどまり、イエスの友ラザロは死んでしまう。やがてイエスは、ラザロの亡骸(なきがら)のあるユダヤに戻ろうとするが、その間、イエスはこう言い続けた。「わたしは彼を起こしに行く」(11節)

しかし、イエスがラザロの墓を見たときの聖書の描写は、それまでとは異なり、きわめて簡潔だ。「イエスは涙を流された」

Why did Jesus weep? The story begins with the sisters of a man named Lazarus sending word to Jesus, saying, “Lord, the one you love is sick.” Jesus immediately reassures them with these words, “This sickness will not end in death.” Then, Jesus dawdles for a while, and his friend dies. Eventually, Jesus returns to Judea, where the body of his friend lies lifeless, all the while reassuring everyone that he will resurrect Lazarus. But then, with his own eyes, he sees the stark tomb of Lazarus himself, and the big, thick, wordy Bible is suddenly pithy in describing the scene: “Jesus wept.”

イエスは、試練を避けて恵みにあずかろうとはされなかった。

Jesus didn’t skip the grit to get to the gift.

彼は全世界の神で、力にあふれ、その言葉には正義と愛がある。イエスは、愛する友を復活させることができる。疑いようもなく確実に、イエスのみが行えるわざだ。

けれども、イエスは涙を流された。イエスは友の死を悲しみ、別れを嘆いた。大っぴらに悲しみを表したのだ。

人は苦しみに対しては、レシートをつけて返品したくなる。できることなら、悲しみはパスして、すぐに復活に到達したいと望む。けれども、人となられた神は違うのだ。

He’s the God of the universe, power with a pulse, justice with a jawbone, love with a larynx. He knows he can and will resurrect his beloved friend—the outcome is not in question, the joy is not in doubt, the gift is not up for grabs—and yet he sobs anyway. He feels the grief and the sorrow, the loss and the agony. He takes time for the pain. To surrender to it. To show it. Though we human beings tend to ask for a receipt and try to return our pain—though we human beings, if given a choice, would skip the weeping and get right to the resurrecting—God-become-human will have none of it.

救いの物語の始まりは、人としての苦しみの物語だった。

Before the gift of the whole story, Jesus makes space for the grit of the human story.

数年経った今、臨床心理学者として私はこう思う。イエスが涙を流したのは、イエスの教えの中で最も大事な部分かもしれないと。「私は信仰的なはずなのに、なぜ将来どうなるかを恐れているのだろう」、「天の国を信じているはずなのに、どうして死別がこれほど悲しいのか」とクライアントが言うとき、聖書の最も短い節、友の復活の前にイエスが涙を流されたことを思い出すのだ。

Now, years later, as my kids fall asleep with visions of Nintendo Switches dancing in their heads, as a clinical psychologist, I think the weeping of Jesus may be one of his most important teachings of all. Now, when my clients say things like, “My faith is strong, so I don’t know why I feel so afraid of all this uncertainty,” or “I believe in heaven, so I don’t know why I feel so sad about all this loss,” I remember the shortest verse in the Bible. I remember that Jesus wept before the resurrection of his friend.

将来への信仰は、今現在の痛みを消し去りはしない。

I remember that faith in the future does not erase our pain about the present.

しばしば私たちは、イエスの復活という恵みばかりを求め、復活に先立つ苦痛に対してはレシートをほしがる。クリスマスは心を静めて、彼の生涯がいかに不完全であったかを振り返るのに最適な時だ。ヒーローにはみな原点の物語があるが、イエスの物語はその初めから痛みや苦悩に満ちている。(次ページに続く)

Oftentimes, we’d prefer to reflect upon the gift of a resurrected Jesus, while we want a receipt for all of the grit that preceded it. But Christmastime is the perfect time to slow down and reflect upon how terribly imperfect his entire life really was. Every hero has an origin story, and Jesus’ story is overflowing with pain and grit, from the very beginning.

「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(Christianity Today)は、1956年に伝道者ビリー・グラハムと編集長カール・ヘンリーにより創刊された、クリスチャンのための定期刊行物。96年、ウェブサイトが開設されて記事掲載が始められた。雑誌は今、500万以上のクリスチャン指導者に毎月届けられ、オンラインの購読者は1000万に上る。

関連