(前編を読む)

──「もう教会には行かないし、自分はもうクリスチャンではない」と誰かが言うとき、それを最終的な答えだと扱うことは簡単です。それをこの対話の結論としようとする誘惑にかられる人々に、あなたは何を伝えたいですか。

When somebody is saying that they’ve left the church and decided they’re not a Christian anymore, it’s easy to treat that as the final word on the subject. What would you say to people who are tempted to treat it as the last word in the conversation?

ドリュー・ディック:誰かが明確に信仰を捨て去り、それを公表するとき、再び教会に戻ってきたり、信仰を取り戻したりすることは難しいでしょう。でも、必ずしもそうだとは断言できないし、絶望的なわけでもありません。信仰に帰属意識を持っていた熱心な信者が転換期を迎えたのならば、将来再び転換期が訪れないとは限らないですよね。信仰の歩みの中で考え方が変わることは必ずありますから、絶望的に思えても、あきらめないよう伝えています。

Drew Dyck: Obviously, if someone has like totally rejected the faith and walked away and made that announcement, it’s hard to get them to come back to church and open to coming back to the faith. I’m not going to pretend it isn’t, but it’s also not hopeless. If that person at one point was a passionate believer and really ascribed to these things and they changed their minds, who’s to say that they won’t change their mind again in the future? People certainly aren’t static in their faith journey, so I encourage people not to give up even when it seems hopeless.

オーストラリアの洗礼者ヨハネ聖公会にあるステンドグラス

私が自称「元クリスチャン」の人々にインタビューしたとき、尋ねた質問の一つは、「まだ祈ることがあるか」でした。驚いたことに、一部を除いたほとんどの人が「まだ祈ることがある」と言ったのです。その祈りは、怒りを含んだ非常に正直で必死さのある祈りで、それは私にとって心強いことでした。たとえ人々が群れから離れたように見える時も、神はその心の中で働かれていると私は信じています。神はあきらめていないし、私たちもあきらめるべきではないと思います。神は99人を残してでも一人を探しに行くような善き羊飼いです。私たちも、同じ思いやコミットメント、そしてその希望を持つべきだと思います。

When I did my interviews all these self-described ex-Christians, one of the questions I asked was if they ever still pray. And I was amazed. Most of them, with a couple of exceptions, admitted that at times they still do. And they were these angry, very honest, desperate sorts of prayers, yet for me that was encouraging. I do believe that God still works in people’s hearts, even when they seem like they have left the fold. So yeah, we don’t want to give up on these people, and I believe God hasn’t given up on them. He’s the Good Shepherd that leaves the 99 to go searching for the one, and we have to have that same heart, that same commitment, and that same hope.

ただ、注意すべきこともあります。「神があなたを連れ戻す」というようなことを言うべきではありません。まず率直に言ってしまえば、それは「あなたには分からないこと」だから。二つ目に、それは信仰を離れようとしている人に対して上から目線であり、否定的な言葉です。無神論者と話すとき、私も同じように感じることがあります。彼らは言います。「そのうち分かりますよ。あなたが賢くて、十分な情報を得ていれば、信仰なんて捨てるでしょう」ってね。そんなことを言われたら、ろくに話も聞かないのに指図されているような気持ちにもなるでしょう。それはあまり意味のある言葉ではありません。「信仰を取り戻してほしい」とあなたが願っていることを伝えるのは良いとしても、「そのうちそれは起こる」と言うのは間違いだと思います。

There is a caveat. You certainly don’t want to say things like, “God will bring you back.” First of all, you don’t know that, if we’re being honest. And secondly. it’s kind of patronizing and dismissive of the current position that they’re in. I know that I feel the same way when I’ve talked with atheists that say, “You’ll see the light, once you get smart enough, you read enough, you’re going to disavow your faith.” It’s like thanks for speaking over my voice and telling me what I’m going to do, right? And so that’s certainly not helpful either. You can express your desire that they would come back to their faith and yet to tell them it’s going to happen, I think it’s a mistake.

──なぜ欧米の人々はキリスト教信仰から離れるのか、統計的観点から教えてもらえますか。50~60年前と比べて、キリスト教を去る人々の数はどう変化しているでしょうか。

Can you tell us statistically why people leave Christianity here in the West? And what’s different about the numbers of people who are leaving Christianity today as opposed to 50 or 60 years ago?

ドリュー・ディック:欧米では、無宗教を主張する人の数が加速度的に増えています。2010年に前述の本を書いたとき、18~30歳の青年層のうち22%は自らを無宗教者と答えています。その多くはクリスチャン家庭で育っています。その前、1990年に取った数字は11%だったことを考えると、大きく上昇しています。それが今では34~36%です。

Drew Dyck: There has definitely been an acceleration in the number of people in the West claiming to have no religion. When I wrote my book in 2010, 22 percent in the younger cohort of 18 to 30 claimed to have no religion. Many of those had grown up in Christian homes. And that was a huge spike because the numbers before that were from 1990 that showed 11 percent. Today, it’s at 34 to 36 percent.

リチャード・ドーキンス(写真:Mike Cornwell)

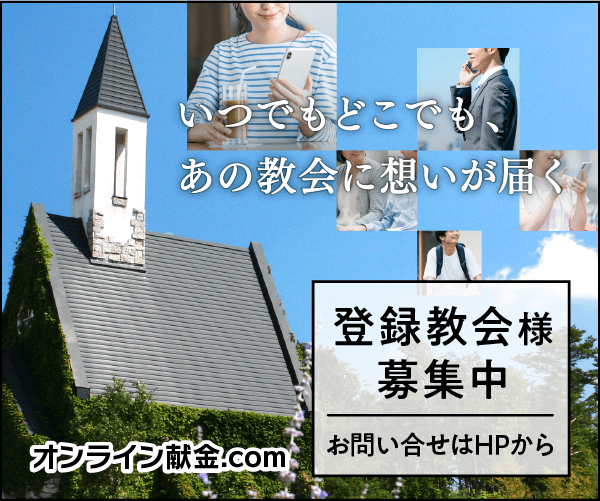

人々が離れる理由については、答えるのが難しいですね。みんながリチャード・ドーキンスやクリストファー・ヒッチェンズの本を読み、感情的な無神論者になったせいでキリスト教を離れることになったと思う人もいるかもしれません。しかし統計的に言えば、小さい頃から持っていた信仰を捨てた大多数の人々は、「だんだんと離れていった」のです。ピュー研究所の調べの一つでは、71%の人々が「だんだんと離れていった」と答えています。そして、そのうちの多くの人々は、信仰に対して大きな壁を持っているわけではありません。

As far as why they leave, that’s a tough one. You might assume that they all leave because they read Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens and became angry atheists. But statistically speaking, the vast majority of people who leave the faith of their childhood do so because “they gradually drifted away”—71 percent, according to one Pew study, reported they just gradually drifted away. And those people often don’t have huge barriers to belief.

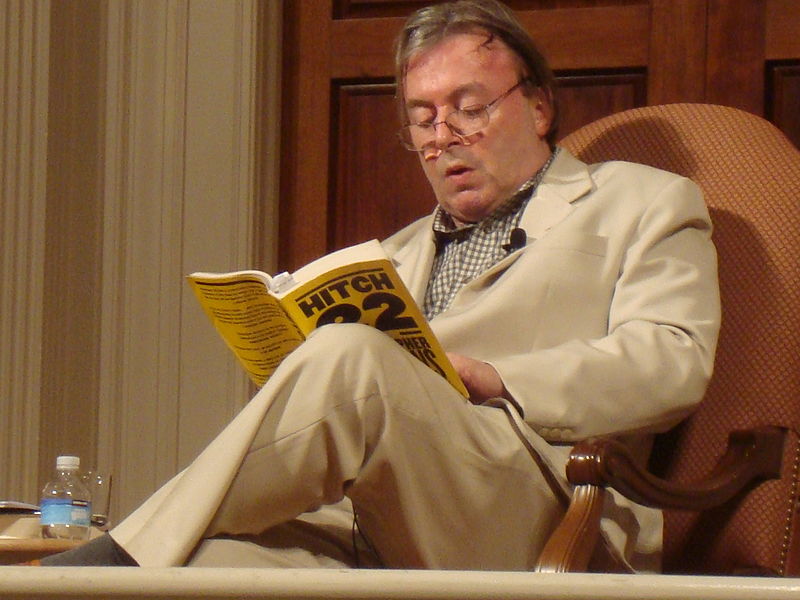

クリストファー・ヒッチェンズ(写真:meesh)

その人々は、神に対して怒っているわけでも、キリスト教の信条や実践に対して論理的に反対しているわけでもありません。つまり人々に必要なのは、隣に来て教会に引き戻してくれる友人や家族なのかもしれません。そして、信仰についてもう一度見つめ直すような機会かもしれません。

They aren’t angry at God or have huge intellectual objections to Christian beliefs and practices. It may just mean they need a Christian friend or family member to come alongside them and kind of pull them back into the church, and kind of a challenge them to take a second look at the faith.

──友人を教会に連れて行こうとする際、どのような姿勢で臨むことを勧めますか。どのような質問をするのがいいでしょう。二人の関係性と相手の考えを尊重しながらも、相手に(信仰との)つながりをもってもらいたいと深く願っていることを知らせる良い方法はあるでしょうか。

What is a posture that you would recommend friends take two friends with regards to this? What are good questions to ask? Or what are good ways to talk about this in a way that respects the relationship and respects the other person, but also lets them know that you care deeply about keeping this part about them engaged?

ドリュー・ディック:パッと思い浮かぶ言葉は「共感」と「好奇心」です。友人が信仰から離れてしまったことを知るとき、詰め寄るようなことがあってはいけないし、挑戦的であってもいけません。その一方で、「それがあなたの道。これが私の道。あなたはそっちに行って、私はこっちに行く」と言うのも良くありません。そのような態度によって伝わるのは一種の無関心です。悲しみを投げつけるのではなくて、こう伝えるのがいいかもしれません。「あなたのことが心配です。私はあなたがどういう状態なのか、知りたいと思っています。あなたの(信仰の)旅路の中で今いる場所、そして、そこへ行き着いた経緯について教えてもらえませんか」。あなたが気にかけ、関心を持っており、その関係を維持したいと伝えるのは良いことだと思います。

Drew Dyck: The words that come to mind for me are empathy and curiosity. You don’t want to be too aggressive and come out swinging when you learn that a friend has walked away from their faith. On the other hand, don’t say, “That’s your journey. This is mine. You do you, I’ll do me.” That kind of attitude can actually convey a sort of indifference. You don’t want to hit them with a lot of grief either, but you want to say, “That’s concerning to me, I’m curious about where you’re at. Can you tell me more about your journey and where you’re at and how you got there?” I think that it’s good for them to know that you care and that you’re interested and that you want to maintain that relationship.

信仰を去る人々の物語を深く聞いていくと、信仰から離れるきっかけの多くは、人間関係の中で起こったことが分かります。青年グループで疎外されているように感じたとか、霊的権威に虐待されたとか、両親との関係に問題を抱えていたといったことです。それが何であれ、(信仰から離れる)理由となっているのです。そのように人生の危機を迎えている人、猜疑心に駆られている人から「信仰的な話をしたい」と頼られるような関係性を持てているなら、それはとても光栄なことですから、その人との絆を維持することは非常に重要だと思います。

So many of these stories of people leaving their faith, if you dig down deep enough into them, the break from their faith actually happened in the context of a relationship. They felt maybe alienated in their youth group, or they were abused by a spiritual authority, or they have relational issues with their parents. Whatever it is, it often plays a role. I think to maintain those relational bonds are crucial so that when that person does have a crisis in their life, or they start doubting their doubts, you are that person that they turn to and it’s a huge honor if you can retain that relationship and be the person that they want to have spiritual conversations with.

──親たちに何かアドバイスはありますか。

What advice do you give to parents?

ドリュー・ディック:センシティブな問題ですね。「親としてどれだけ身近な存在であるかということを心に留めておくこと」でしょうか。子どもが信仰から離れていこうとするのは、あなたに対するちょっとした反抗であることがしばしばです。子どもとの関係性を危うくしてまで、信仰について議論することは避けるべきです。あなたの息子、娘として肯定することについて、親は本当に注意を払わなくてはいけません。

Drew Dyck: That’s a dicey one. Beware of how you have an incredibly close relationship with this person as their parent. Often when they’re walking away from their faith, sometimes they’re pushing back against you a little bit. You don’t want to make the relationship they have with you a referendum on God. And so this is where you really have to be careful in affirming and loving of them as your son, as your daughter.

両親から説教され、「地獄に行く」と言われ、叩きのめされたせいで、こういった会話をすることができなくなった多くの人と私は話をしてきました。そして、それはタブーになってしまいます。たとえ両親との関係性を維持していても、話したくないトピックになってしまうのです。だから(親は)本当に優しく、繊細に、そしてオープンに話せるよう努力しないといけません。ただこう言うだけでもいいんです。「私は心配なんだ。信仰については、おまえとは違う価値観を持っているけど、対話は続けたい。おまえを裁くつもりも説教するつもりもない。おまえがその話をしたいと思う時が来たら、私はいつでもここにいるよ」

I’ve talked to so many people they will not have these conversations with their parents because their parents have preached at them, they told them they’re going to hell, they have just ripped into them, and it becomes the sore point even if they stay connected to their parents. It’s just like a no-go topic for them. So really work hard to be gentle, sensitive, and open. And you can even just say, “Hey, I’m concerned. I know we’re at different places when it comes to God. I’d love to continue the conversation. I’m not here to judge you. I’m not here to preach at you. But anytime you want to talk about it, I’m here.”

よく思うことなのですが、自分の愛する人が信仰を捨てるとき、それは驚くほど人々を不快にさせ、心配が勝るために、喜んで信仰に生きる代わりに、こうした不機嫌な態度を取らせてしまうのです。まるで(「くまのプーさん」の)イーヨーのような態度を取ってしまうんですね。むしろ、信仰によって喜びを得ていること、それによって人生が豊かになっていること、そしてあなたがイエスに心から従っていることを示したほうがいいと思います。結局のところ、(信仰の価値を証明する)最高の方法は、キリストのために生きている姿だからです。あなたがそれを、愛する人々に見せることができるならば、それはとても大きなことです。

I think so often a lot of people when they have a loved one that leaves the faith, it’s incredibly disconcerting to you and instead of joyfully living out your faith you actually adopt this dour demeanor because you are so concerned about it. And so whenever you’re around this person, you’re like an Eeyore or something. You want to show that you’re still enjoying your faith, that it’s something that’s enriching your life, and that you’re still passionately following Jesus. Because ultimately the best apologetic is a life lived for Christ. And so if you can demonstrate that to the people that you love, that’s huge.

──自分が原因でその人を信仰から離れさせたとき、どう受け止めるべきでしょうか。謝罪するのが適切だと思いますか。

What kind of ownership do you think a person of faith should take for the failings that somebody experienced that may have led them to renounce their faith? Do you think it’s appropriate to apologize?

ドリュー・ディック:謝罪するのが適切だと思います。尊敬しているクリスチャンから虐待されたとき、または不当に扱われたとき、それが悪かったと言ってもらうことは絶対に不可欠です。クリスチャンから、それが間違いだったと認めてもらい、本来どうあるべきだったかを聞くことは、被害者にとって大きな慰めになると思います。なぜなら、このことに関して最も危険なのは、被害者が虐待者を神と同一視して、すべてを投げ出してしまうことだからです。

Drew Dyck: I think it is appropriate to apologize for it. When someone was abused by someone they looked up to as a Christian or they are treated unfairly, It’s absolutely essential to express that empathy. I think it’s very healing for them to hear from a Christian that that was wrong, that should have happened. Because the biggest danger when it comes to these topics is that they kind of conflate the abuser with God and toss everything out.

ですから、もしあなたが感情的になってしまったとしても、「神の名のもとに虐待を行う人」と「神」との間に明確な区別をつけることができれば、それは大きな前進です。それが最初にやるべきことだと思います。間違ったことをしてしまったと、ただ認めること。ただし、すぐに「それはイエス様ではない」とか「それが真のキリスト教ではない」と主張してはいけません。彼らはまだそれを聞く準備ができていないかもしれないから。「全面的に間違っていた」、「あなたの気持ちを想像して怒りを覚える」、「あなたのために悲しんでいる」、「私はあなたの話を聞きたい」と言うだけでいいのです。

And so if you can help them, even emotionally, make that crucial differentiation between God and the person who mistreated them in God’s name, that’s huge. So I think that’s the first thing to do: just to acknowledge that what happened is wrong. And then don’t also jump right in to argue that that’s not like Jesus or that’s not true Christianity. Because they may not be ready to hear that quite yet, but just an unqualified that was wrong, I feel angry for you, I’m sad for you, I hear you.

──当然のことながら、牧師が自らの信仰の悩みについて公にすることは少し変な感じがすると思います。しかし、牧師が苦闘しているかどうか分からなくても、教会員が牧師を支える方法はあるでしょうか。

Obviously, it’s going to be a little bit strange for pastors to publicly dialogue with their congregations about where they are with their faith at any given time. But what are ways for congregants to support their pastors even unknowingly as they might be wrestling?

カイル・ロヘイン:牧師には羊飼いの役割があり、霊的な親の役割も担っていると認めつつ、それでも牧師も人間だと意識することが本当に重要だと思います。牧師は苦しい1週間を過ごしたかもしれないし、その苦しみがキリストや神との関係に影響を与えたかもしれません。牧師は、その肩書によって守られているわけではないのです。牧師がそれを求めなくても、励ましてあげてください。「先生、疲れているんじゃないですか。私たち家族は先生のために祈っていますよ。先生のことが心配なんです」と伝えてもいいでしょう。誰にとってもそうであるように、それは牧師にとってもすごくありがたい言葉なのです。

Kyle Rohane: I think it’s really important that while we accept the fact that our pastor is in the role of Shepherd, is in the role of spiritual parent, that they are still human. That they may have had a bad week and that bad week has an effect on their relationship with Christ and with God, that pastors aren’t shielded from those things just by virtue of having the title pastor. And offering their pastor encouragement, when the pastor doesn’t have to ask for it. That you can go unsolicited and say, “Hey, I see that you look tired this week. I just know that my family and I are praying for you and we care for you deeply.” I think that is amazingly helpful for a pastor, just as it would be for anybody.

ドリュー・ディック:ええ、そうだと思います。牧師は他の人たちと同じように疑いや落胆に傷つきやすいばかりでなく、信仰についてさらなる挑戦を受ける立場にあります。注意しなければ、他人の魂をケアすることが、自らの魂をないがしろにすることにつながりかねません。しかし、教会員ができることはたくさんあるとは思いません。牧師には対話の相手、心から素直に自らの疑問をあらわにできる相手を必要としているのではないでしょうか。他のリーダーや、たとえ教会外にいる人でも、心から率直に話せる相手を見つける必要があります。多くの牧師は疲れ果てているので、牧師同士で話す機会があってもいいのではないでしょうか。(前編を読む)

Drew Dyck: Yeah, I love that. Not only are pastors just like the rest of us and susceptible to doubt and discouragement, but ministry comes with even extra challenges to your faith. Tending to the souls of others can, if you’re not careful, really be hard on yours. But I really don’t I think there’s much we can do as congregants. I think pastors need dialogue partners, people with whom they can be completely honest with to air their doubts. They need to find other leaders, maybe even people outside of their own congregation, that they can be completely transparent with. Because that relationship between the parishioner pastors so fraught.

執筆者:モーガン・リー

本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。

出典URL:https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2019/july-web-only/leaving-faith-church-christianity-falling-away-josh-harris.html

「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(Christianity Today)は、1956年に伝道者ビリー・グラハムと編集長カール・ヘンリーにより創刊された、クリスチャンのための定期刊行物。96年、ウェブサイトが開設されて記事掲載が始められた。雑誌は今、500万以上のクリスチャン指導者に毎月届けられ、オンラインの購読者は1000万に上る。

関連